So, how does one read a poem? I like to look at the beginning line and the end line to see where the poet enters and where the poet leaves.

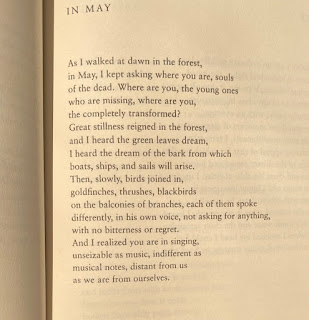

In this wonderful poem by Adam Zagajewski, the opening line immediately has a narrator ("I"), action, and setting. The I might be the poet himself, or it might be a persona that the poet has created for this narrative. Ambiguity in a poem is common. It allows the reader to find more than one meaning. "I" could even refer to the reader.

Then, the pronoun "you" refers to the souls of the dead. The poem appears to be addressed to the souls. The narrator asks "where are you?" It is an existential moment, definitely. After the question, the forest images predominate. Using figurative language, the narrator says, "I heard the green leaves dream./ I heard the dream of the bark from which/ boats, ships and sails will arise." Figures of speech, or figurative language, is characteristic of many poems. Metaphors use one thing to explain something else. Imaginative images and scenes like this give the reader a vision of time and beautiful transformations. Then the birds come in "on the balconies of branches," each singing a unique song "...not asking for anything, with no bitterness or regret,/" Here the birds are described in human terms.

Next, a turn. A leap. In a sonnet, this shift is called a volta. I like to think of this moment as similar to a bend in the river that brings you to a new vista. It brings us to the ending: "I realized you are in singing..." The ending line has a new pronoun, not "I" or not "you" which have occurred in the earlier lines, but "we." The word signals a shift. Now the narrator and souls are drawn together as a we, or perhaps it's the narrator and audience or readers that are drawn together. It's a satisfying answer to the initial question.

Repeated words, phrases or images are important. Rhythm and sound are important, because all of this forms a kind of music. In this poem, it is a call and response form. "Where are you? ....Where are you?" and "I heard... I heard..." and then, "...you (souls of the dead) are in singing,/ unseizable as music, indifferent as/ musical notes, distant from us/ as we are from ourselves."

Unseizable. A lovely word and a lovely rhythm in this phrase. Notice the line breaks. A line break does create a sort of pause, a hesitation, and here the line break that occurs after "distant from us" (of course, the birds are distant because they are far above and of course souls of the dead are far) does something new. There is a subtle shift, for the next line reads "as we are from ourselves." Now that's surprising. The poet is saying that we don't know ourselves, that we have parts of our being we cannot easily reach, and perhaps we cannot ever reach. The ambiguity expands meaning. He might mean himself, he might mean the reader.

A poem like this captures a moment, a place, and a person who has longing. It speaks of spiritual truths to the reader: we have loss, a connection to the souls of the dead. We have lost loved ones, friends, people in our community, and we have also been aware of an internal loss, the inability to know our own self, our connection to our own being. The phrase "Where are you?" now takes on this new meaning.

In just a few lines on the page, this poem says so much concisely. The words and images have beauty. One poet said that poems are made of forces. If so, what are the forces operating inside this poem? There are no definitive answers, no right interpretation or wrong interpretation, only things to ponder. There are impressions. Resonances. Echoes. There is breath. There is light and music.

To find out more about this poet, go to https://poets.org/poet/adam-zagajewski

No comments:

Post a Comment