Here is an excerpt from her book in Finnish:

Laakakatajat, haahkat, tyrnit,

rahkasammalta kasvavat kalliot

vanhan meren loppumaton kohina

Vain tämä silmiini kivettyvä maisema

jää jälkeeni maailmalle,

veteen heitetyn kiven synnyttämä aaltoilu,In conversation, we explored the question of how all of our writing might relate to Finnish identity. It is an interesting question, and the answers were diverse. They are elusive. In the culture, people might say Finnish-ness includes independence and determination, a quietness or reserve, a connection to nature and landscape, and also inexpressible longing.

kaarenkestoinen onni, täydellinen...

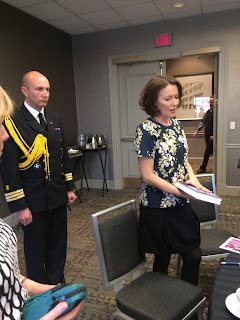

In the photo from left to right: Suzanne Matson, Diane Jarvi, Liisa Virtamo, Jenni Haukio, Ann Tuomi, Beth Virtanen, Christina Maki and Donna Salli in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Elbows of reeds, hawks, gulls,

the moss-faces of rocks

in the endless noise of the old sea

Only in this eyed landscape

I'm behind the world,

a ripple caused by a stone thrown far into the water,

a concentric orbit of luck, widening

(Translated by Sheila Packa)